Cataloguing the Sixth Mass Extinction Part VI

As we enter 2023, no cause for climate optimism has emerged. The awareness of our predicament and of our capability to drastically mitigate it has increased, but this potential continues to be wasted.

Previous entries:

Cataloguing the Sixth Mass Extinction Part I

Cataloguing the Sixth Mass Extinction Part II

Cataloguing the Sixth Mass Extinction Part III

Cataloguing the Sixth Mass Extinction Part IV

Cataloguing the Sixth Mass Extinction Part V

On Wednesday, the United Arab Emirates, who will preside over this year’s UN climate change summit, announced that the president of November’s COP28 talks will be this man, a well-connected energy and industrial insider named Sultan Al Jaber:

Sultan Al Jaber has served as climate envoy to the country, and is chief of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (Adnoc), the world’s twelfth-largest oil company by production, and is hotly tipped to take on the pivotal role of president of the talks.

He is also minister of industry and advanced technology for UAE, and head of the Masdar company, which focuses on renewable energy.

The Cop28 UN climate summit, which will take place from 30 November in Dubai, will be a crucial conference, determining whether the world can get on track to tackle the climate crisis. This year, nations must conduct a “global stocktake” assessing the current state of climate action and progress on fulfilling the goals of the 2015 Paris agreement.

While some countries have submitted national plans to cut greenhouse gas emissions that are in line with the ambition in the Paris agreement of limiting global heating to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, many of the world’s biggest emitters have failed to do so, imperilling the climate goals.

One of the roles of the presidency will be to hold such recalcitrant governments to account, but many observers fear that UAE, as a major oil producer and with close ties to other producers such as Saudi Arabia, will be reluctant to take them on.

At Cop27, held in Egypt last November, there were scores of oil and gas lobbyists from UAE, and Gulf states with strong oil and gas interests were thought to have been among the blockers preventing stronger language on phasing down fossil fuels.

The site for the upcoming Atlantic Council Global Energy Forum states that Dr. Al Jaber “oversees efforts to further expand the industrial development of the UAE,” works to “increase industrial competitiveness,” and that as CEO of ADNOC has “fostered a more commercial mindset.” He is a leader of “UAE’s clean energy agenda at Masdar, Abu Dhabi’s pioneering renewable energy initiative.” What is Masdar? The company does invest in solar, wind, and other renewables, but its site also claims that it is a leader in developing green hydrogen technology, an expensive and therefore rare method of producing low-emissions energy:

Masdar is seeking to become one of the world’s leading players in the growing green hydrogen econpmy[sic], one of the company’s executive directors told Energy Intelligence. As one of the world’s leading clean energy companies, Masdar has set its sights on becoming a hub for the production and export of green hydrogen, Mohammed Abdelqader El-Ramahi, Masdar’s Executive Director for Hydrogen, said in an interview.

From the journal Capital Nature Socialism:

Experts such Birol, build on the long-standing idea that a hydrogen utopia will be green, but the realities of our carbon lock-in suggest that it will be fossil fuel-based for the foreseeable future. Green hydrogen production is in its infancy, meaning that it is not yet economically viable, nor has it been scaled up to produce energy on a large scale. The largest hydrogen electrolyser has an installed capacity of 6 MW, which is set to be followed by other projects adding 5–30 MW apiece (Collins 2020). These are dwarfed by the existing hydrogen production capacities already used by oil refineries, for example. Dedicated pure hydrogen production is currently intimately linked to the hydrocarbon industry, since the oil refining industry is the prime user of hydrogen as a petrochemical for hydrocracking and desulphurisation. Industry incumbents carry the know-how and have already constructed vast hydrogen production infrastructures. The oil and ammonia industries predominantly rely on steam methane reformers to produce pure hydrogen, a natural gas-based process with a high operational efficiency and low production costs (IEA 2019)…

Proliferating fossil fuel combustion has led to heightened greenhouse gas emissions, ushering in an era of anthropogenic climate change. This has turned into a climate crisis that poses a rupture to the dominant power relations predicated on fossil fuels, since most of global society’s efforts to decarbonise will have to be directed at its energy system (Scrase et al. 2009). Renewables, such as solar photovoltaics and wind power plants, carry disruptive potential that recalibrate carbon lock-ins. However, they are unable to institute all-encompassing change, in-part due to technological limitations. We are unable to (economically) electrify social practices currently in place, while electricity storage to enable electrification on a grand scale is also lacking (Sivaram 2018). This is further inhibited with the existing lock-ins of fossil capitalism. Key fossil fuel actors have drawn on the carbon lock-in to promulgate their vision of the future. Hydrogen is at the heart of this strategy, since it is a source of energy that sustains decarbonised fossil capitalism.

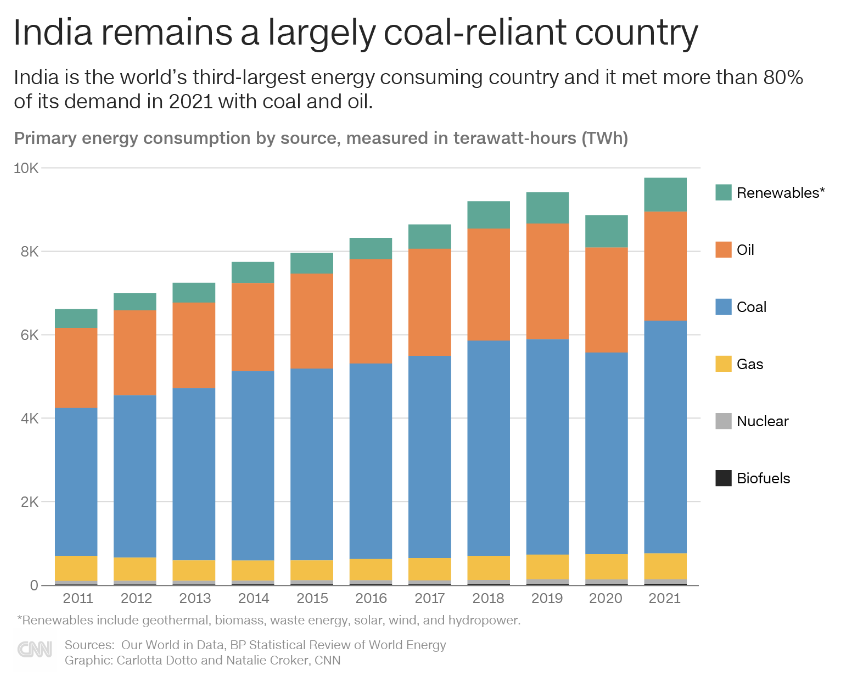

Al Jaber is also the recipient of “a lifetime achievement award from His Excellency the prime minister of India, Narendra Modi, for his contributions to energy security, building bridges to emerging Asian economies and for reshaping traditional energy business models.” Of course, the far-right Modi’s India emits as much total carbon as the entire EU, and its emissions increased by 10.5% in 2021:

India emits over 2.4 billion tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) a year based on data collected by the EU. An analysis of its plans by the Climate Action Tracker show that the country’s goals are “critically insufficient” to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above levels before industrialization. Warming beyond that threshold will trigger irreversible damage and push many ecosystems to tipping points, climate science shows.

The UAE as well has a high carbon footprint, yet has only claimed the goal of net zero by 2050:

The UAE relies heavily on the export of oil and gas, which makes up about 30% of its gross domestic product, despite decades of efforts to diversify the economy. The nation of 10 million people also has one of the world’s highest emissions rates per capita — ahead of the likes of Australia and the U.S.

Dr. Jaber’s career is emblematic of this sort of greenwashing doublespeak, offering solutions which are at best too little too late to avert major disaster and at worst, actively harmful policies which invalidate the possibility of direly needed reforms. Bloomberg:

Yet under Al Jaber’s leadership, ADNOC plans to increase its oil production to 5 million barrels a day by 2027 from 3 million. This jibes with the UAE climate envoy office’s views on the energy transition. It doesn’t see climate action as a matter of flipping a switch on fossil fuels. With energy demand increasing, some see natural gas and oil as a way to bridge the gap and maintain energy security while renewable infrastructure is put into place.

In a statement on his COP28 appointment, Al Jaber says he’ll bring “a pragmatic, realistic and solutions-orientated approach” to the annual gathering. It might be pragmatic, but it still sets the pace for change — which scientists agree needs to be rapid — to slow. And many stakeholders will not see “more oil” as a reasonable solution, especially when the president setting the COP agenda has a commercial interest in growing his oil business for years to come.

The world can no longer abide this kind of doublespeak:

At present, humanity is on a path to between 2.2 °C and 3.4 °C of warming, with 2.4 °C the most likely value if countries deliver on the emissions reductions they promised to make by 2030, according to the Climate Action Tracker, an independent group of researchers that monitors government action on climate. But temperature increases are likely to be at the higher end of the range if pledges are not kept and business continues as usual.

(Why fossil fuel subsidies are so hard to kill)

If 1.5 °C is to be achieved, the world must immediately halt new oil and gas development and transition rapidly to renewable energy. That’s one of the conclusions of a cross-party report from members of the UK House of Commons, which was published last week (see go.nature.com/3qqkthx). The report draws extensively on evidence from the research community, including the parliamentarians’ expert adviser Jim Watson, the director of the UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources in London.

Nor can these industry insiders turned “climate leaders” claim ignorance or good intentions:

In the late 1970s, scientists at Exxon fitted one of the company’s supertankers with state-of-the-art equipment to measure carbon dioxide in the ocean and in the air, an early example of substantial research the oil giant conducted into the science of climate change.

A new study published Thursday in the journal Science found that over the next decades, Exxon’s scientists made remarkably accurate projections of just how much burning fossil fuels would warm the planet. Their projections were as accurate, and sometimes even more so, as those of independent academic and government models.

Yet for years, the oil giant publicly cast doubt on climate science, and cautioned against any drastic move away from burning fossil fuels, the main driver of climate change. Exxon also ran a public relations program — including ads that ran in The New York Times — emphasizing uncertainties in the scientific research on global warming.

Yet scientists who speak up about climate change are routinely retaliated against by employers and the justice system:

Shortly after the New Year, I was fired from Oak Ridge National Laboratory after urging fellow scientists to take action on climate change. At the American Geophysical Union meeting in December, just before speakers took the stage for a plenary session, my fellow climate scientist Peter Kalmus and I unfurled a banner that read, “Out of the lab & into the streets.” In the few seconds before the banner was ripped from our hands, we implored our colleagues to use their leverage as scientists to wake the public up to the dying planet.

Soon after this brief action, the A.G.U., an organization with 60,000 members in the earth and space sciences, expelled us from the conference and withdrew the research that we presented that week from the program. Eventually it began a professional misconduct inquiry. (It’s ongoing.)

Then, on Jan. 3, Oak Ridge, the laboratory outside Knoxville where I had worked as an associate scientist for one year, terminated my employment. I am the first earth scientist I know of to be fired for climate activism. I fear I will not be the last.

Oak Ridge said it was forced to fire me because I misused government resources by engaging in a personal activity on a work trip and because I did not adhere to its code of business ethics and conduct. The code has points on scientific integrity, maintaining the institution’s reputation and using government resources “only as authorized and appropriate and with integrity, responsibility and care.”

When Dr. Kalmus and I decided to make our statement during the lunch plenary session, I knew that we risked being asked to leave the stage or the conference. But I did not expect that our research would be removed from the program or that I would lose my job. When I began participating in climate actions with other scientists in 2022, senior managers at Oak Ridge asked that I make it clear to the public and the media that I spoke and acted on my own behalf. I followed these guidelines to the best of my ability, including at the A.G.U., where Dr. Kalmus, a scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and I did not mention our institutions in our statements.

Put simply, the knowledge of the dangers posed to everyone by these emissions, combined with retaliatory efforts against protesters and campaigners and the disregard for human lives in these companies’ single-minded haste to grow profits, constitutes malice aforethought and therefore organized mass murder on the part of these insiders, and Dr. Al Jaber is no different. He represents the further corruption of climate organizing by the ownership class, who can no longer effectively deny the reality of climate change and environmental destruction, and so work to exploit and derail putatively “green” movements and initiatives in the name of preserving free market arrangements, as recently discussed in this review of Adrienne Buller's The Value of a Whale.

Other recent developments have only amplified the urgency of drastic action and the disappointingly wide gulf between the potential for revolutionary mitigation efforts (even in 2023) and the actual efforts put forth.

They say history repeats, but usually they don’t mean it quite this literally. The global average surface temperature in 2021 ended up ranking fifth warmest or sixth warmest, depending on the dataset. We now have the tally for 2022—and it’s the new fifth or sixth warmest, depending on the dataset…

Looking ahead, expectations are actually also similar to last year. The forecast is trending toward neutral conditions (in between La Niña and El Niño) by late spring. Last year, La Niña returned soon after, so the impact was small, but sustained neutral conditions would boost 2023 a bit above 2022 in the ranking. And if it fully transitions over to El Niño in the fall, the odds of 2024 setting a new record would then be pretty strong.

On 15 January 2022, the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai (HTHH) eruption injected 146 MtH2O and 0.42 MtSO2 into the stratosphere. This large water vapour perturbation means that HTHH will probably increase the net radiative forcing, unusual for a large volcanic eruption, increasing the chance of the global surface temperature anomaly temporarily exceeding 1.5 °C over the coming decade. Here we estimate the radiative response to the HTHH eruption and derive the increased risk that the global mean surface temperature anomaly shortly exceeds 1.5 °C following the eruption. We show that HTHH has a tangible impact of the chance of imminent 1.5 °C exceedance (increasing the chance of at least one of the next 5 years exceeding 1.5 °C by 7%), but the level of climate policy ambition, particularly the mitigation of short-lived climate pollutants, dominates the 1.5 °C exceedance outlook over decadal timescales.

About a quarter of the world's electricity currently comes from power plants fired by natural gas. These contribute significantly to global greenhouse gas emissions (amounting to 10% of energy-related emissions according to the most recent figures from 2017) and climate change. By gathering data from 108 countries around the world and quantifying the emissions by country, a team has estimated that total global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the life cycle of gas-fired power is 3.6 billion tonnes each year. They found that this amount could be reduced by as much as 71% if a variety of mitigation options were used around the world.

The principle that the producer of pollution should pay for its clean-up is established around the world, but has never been applied to the climate crisis.

Yet technology to capture and store carbon dioxide underground is advancing, and is now technically feasible, according to Myles Allen, a professor of geosystems science at the University of Oxford.

“The technology exists – what has always been lacking is effective policy,” he said. “The failure has been policy, not technology – we know how to do this.”

The companies that profit from extracting fossil fuels – oil, gas and coal producers around the world – should be paying for an equivalent quantity of carbon dioxide to be stored geologically as a condition of being allowed to operate, he argued.

The Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, has officially launched the “world’s longest river cruise” from the city of Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh. The luxury voyage will last 51 days, travelling 3,200km via Dhaka in Bangladesh to Dibrugarh in Assam, crossing 27 river systems.

The three-deck MV Ganga Vilas, with 18 suites, is the latest venture in a trend for cruise tourism in India being promoted by the government. Modi hailed the cruise industry on the Ganges as a “landmark moment”, which will herald a new age of tourism in India.

However, environmentalists and conservationists say the rise in cruises could do lasting damage to the habitat of the Ganges river dolphin (Platanista gangetica)…

“The cruises are a dangerous proposition in addition to all the existing risks for the dolphins,” said Ravindra Kumar Sinha, whose conservation efforts led the government to designate Gangetic dolphins as a protected species in the 1990s. Their numbers have risen in recent years, with about 3,200 in the Ganges and 500 in the Brahmaputra, due to improved water conditions and conservation initiatives. But Sinha fears cruise tourism will undo these gains.

Emissions ticked up 1.3 percent even as renewable energy surpassed coal power nationwide for the first time in over six decades, with wind, solar and hydropower generating 22 percent of the country’s electricity compared with 20 percent from coal. Growth in natural gas power generation also compensated for coal’s decline.

The new estimate puts nationwide emissions back in line with their long-term trajectory after nearly two years of Covid-related disruptions, said Ben King, an associate director at the Rhodium Group and an author of the report.

“We are essentially on the same trajectory that we’ve been on since the mid 2000s,” he said, calling it a “long-term structural decline,” but one that’s “not happening fast enough.”

In a healthy rainforest, the concentration of carbon should decline as you approach the canopy from above, because trees are drawing the element out of the atmosphere and turning it into wood through photosynthesis. In 2010, when Gatti started running two flights a month at each of four different spots in the Brazilian Amazon, she expected to confirm this. But her samples showed the opposite: At lower altitudes, the ratio of carbon increased. This suggested that emissions from the slashing and burning of trees — the preferred method for clearing fields in the Amazon — were actually exceeding the forest’s capacity to absorb carbon. At first Gatti was sure it was an anomaly caused by a passing drought. But the trend not only persisted into wetter years; it intensified.

For a while Gatti simply refused to believe her own data. She even became depressed. She had always felt a deep connection to nature. As a kid in a distant town called Cafelândia, she would climb a tree in front of her house, spending hours in a formation of branches that seemed custom-made to cradle her arms, legs and head. In later years, no matter how many times she flew over the Amazon, she never got used to the sight of freshly paved highways, new dirt roads always branching off them, forming a fish-bone pattern. Sometimes she soared past columns of beige smoke that rose all the way to the stratosphere.

As the peak of Antarctica’s melt season approaches, surface snow melting has been widespread over coastal West Antarctica, with much of the low-lying areas of the Peninsula and northern West Antarctic coastline showing 5 to 10 days more melting than average. However, much of the East Antarctic coast is near average. Snowfall in Antarctica for the past year has been exceptionally high as a result of an above average warm and wet winter and spring.

Antarctic surface snow melting through January 10 is above average and reached near-record extent in late December. A significant melt event spread over the Peninsula and across much of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet northern coast and into the Ross Ice Shelf area (Figure 1a). Melting has been moderately above average for the Peninsula areas, but unusually high in the Getz Ice Shelf area, where melting is less frequent. The Larsen Ice Shelf area has seen up to 25 days of melting, about 5 more than average, and the Wilkins region up to 30 days, again about 5 more than average (Figure 1b). The Getz and Sulzberger Ice Shelves (to the lower left of the Antarctic maps) have seen 10 melt days this season, about double the average for this time of year. East Antarctic Ice Shelves—Fimbul, Roi Baudouin, and Amery—have had near-average to slightly above-average melting of 5 to 10 days each.

John Abraham, a professor at the University of St. Thomas, is among more than a dozen scientists who revealed this week the ocean in 2022 was "the hottest ever recorded by humans." It increased by 10.9 Zetta Joules, an amount of energy equivalent to the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima and an amount of heat about 100 times more than the electricity generated worldwide in 2021.

Four basins of the seven world ocean regions – the North Pacific, North Atlantic, Mediterranean and southern oceans – had the highest heat records since the 1950s.

This marks the fourth time in a row that ocean heat content has surpassed records broken the year prior. And while it may seem like a "broken record" at this point, Abraham said this is anything but "normal."

"This is a continuing, ongoing trend," he said. "It's getting worse every year."

It is indeed “getting worse every year.” Even now, it does not have to be this way.